- Council of the Great City Schools

- Federal Funds Helped Atlanta Public Schools Boost Student Attendance and Achievement

Digital Urban Educator - May 2025

Page Navigation

- Political Analyst, Radio Host, and Acclaimed Actor to Address Urban School Leaders at Conference

- Louisville and Fresno Name New Superintendents; Seattle Leader to Step Down

- Long Beach Unified Opens Center of Black Student Excellence

- Toledo Urban Educator of the Year Awards $10,000 Green-Garner Scholarship to Two Students

- Chicago School Wins Urban Debate Championship for the Second Year in a Row

- Federal Funds Helped Atlanta Public Schools Boost Student Attendance and Achievement

- Voters Approve $1.83 Billion Bond for Portland Public Schools

Federal Funds Helped Atlanta Public Schools Boost Student Attendance and Achievement

-

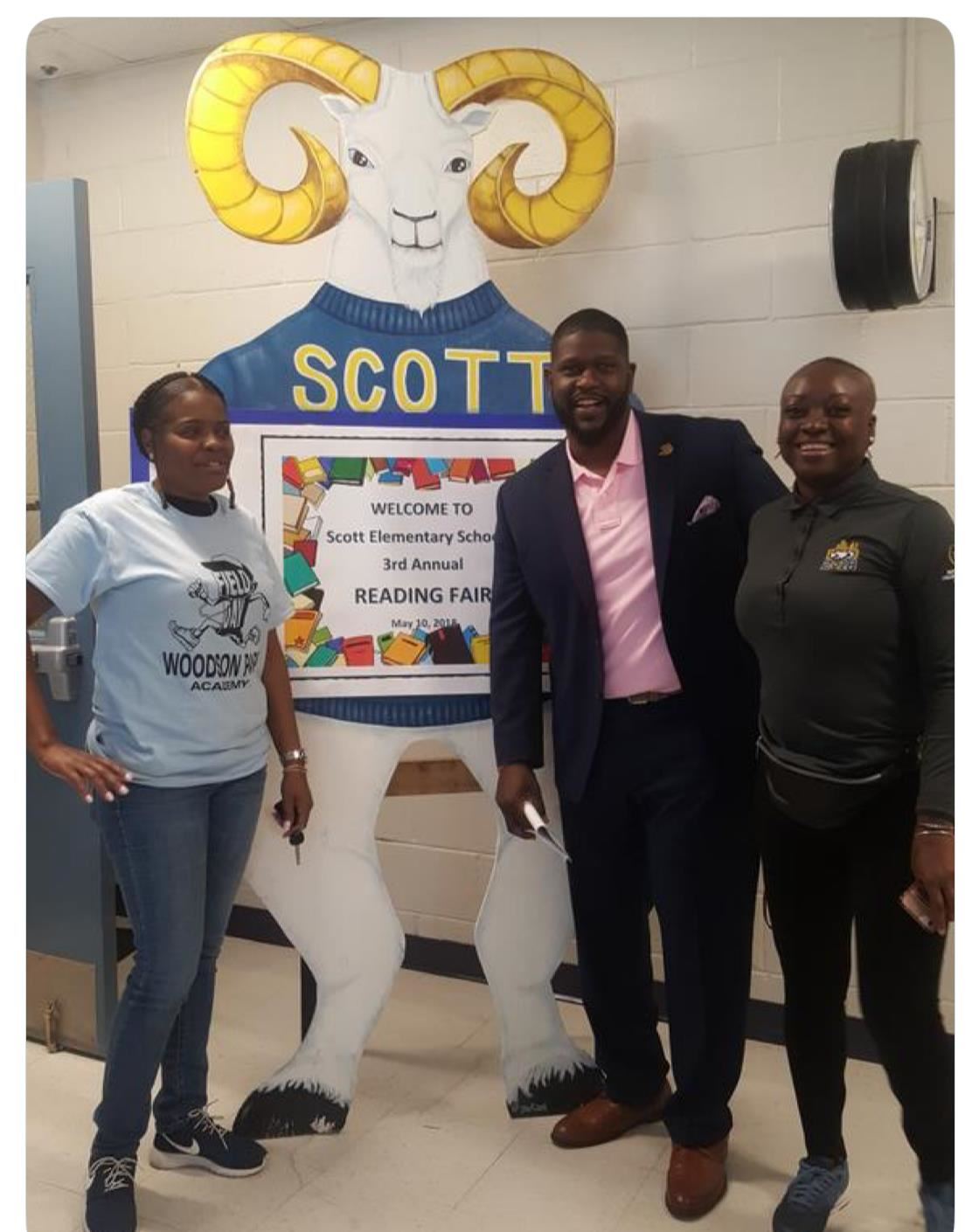

Since Willam J. Scott Elementary started welcoming back students into the building in 2022 after the COVID-19 pandemic forced it and other Atlanta Public Schools to close their doors, the school community has had much to celebrate, thanks to two federally funded programs that have helped boost student attendance and growth in math.

Pandemic school emergency funds helped Scott and other Atlanta elementary schools add a 30-minute intervention block at the beginning of the school day to close pandemic learning gaps. But the recent loss of those funds and the uncertainty about the U.S. Department of Education’s future has the school's leader and his staff scrambling to sustain the momentum.

“We are left trying to do almost the impossible with even less,” Scott principal Langston Longley said.

Thirty-minute intervention block helps students and parents

Not only are Scott’s students, most of whom are Black or Hispanic and many of them from families experiencing chronic financial insecurity, doing better academically, but a federally funded after-school program coupled with the intervention block extended Scott’s school day, enabling many parents at the STEAM-focused school to maintain steady employment. (The elementary schedule for the Atlanta school district changed from 8 a.m. – 2:30 p.m. to 8:30 a.m. – 3:30 p.m.)

Both initiatives “allowed a lot of people to get back to work,” Longley explained. He said many Scott parents work shift-based jobs that require employees to be on-site for eight or nine hours at a time, making it difficult to pick up their children when the school day ends.

Before the pandemic, Scott’s student academic achievement was among the lowest in the district. The pandemic, Longley said, worsened student progress.

“Coming out of the pandemic, any area of deficiency [for students] was supercharged,” Longley, who’s been at Scott’s helm for 10 years, said.

Longley and his staff knew the school needed to strike a balance between maintaining standards-aligned, grade-level instruction and executing a new strategic focus on helping students overcome their individual academic challenges.

The challenge was compounded by the variation in student academic loss during the pandemic. Students’ progress during remote learning “was all over the place,” Longley said. “A teacher’s ability to differentiate for 25 kids was really challenged.”

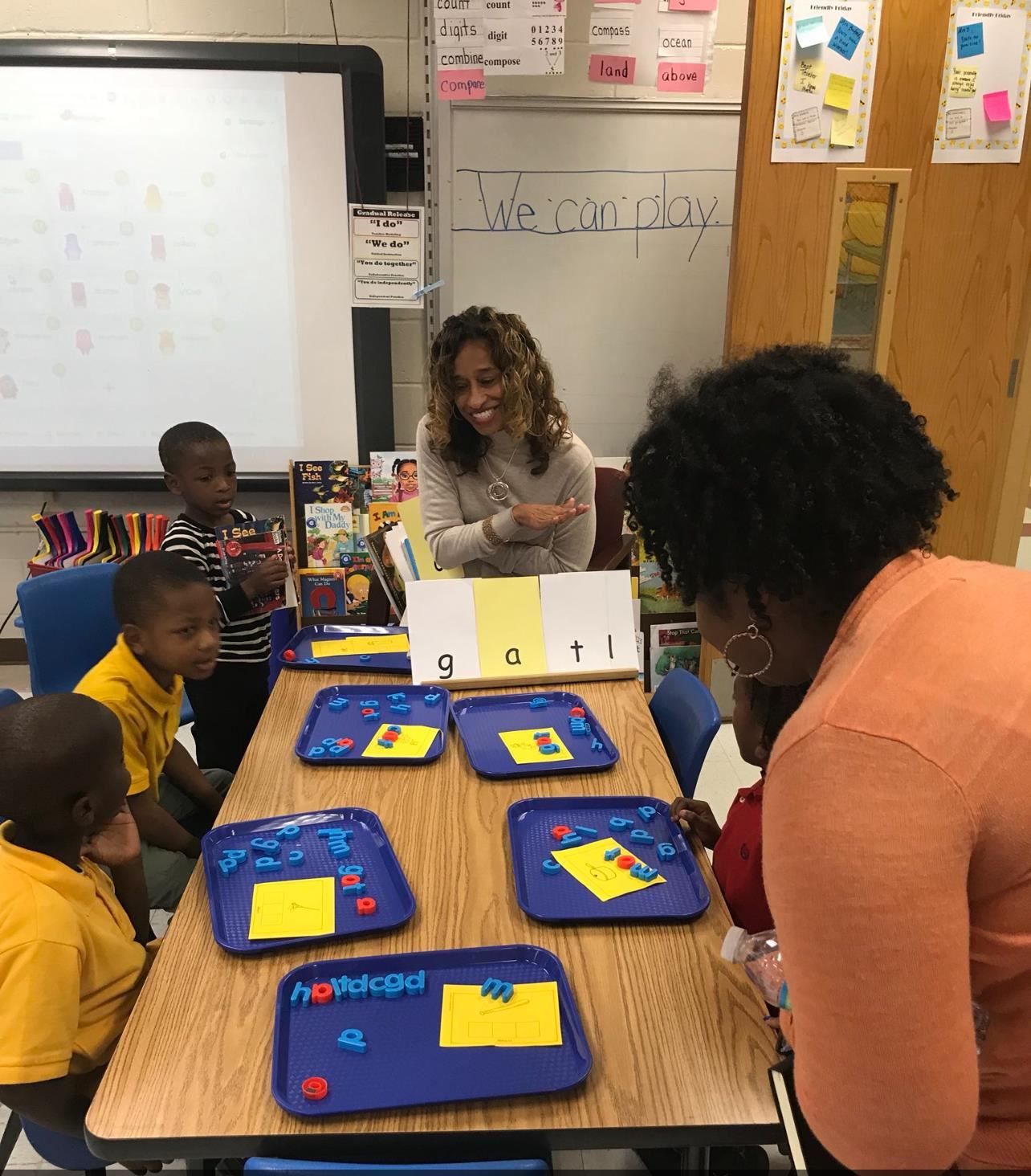

The answer for Atlanta administrators and Scott Elementary was more in-person time between students and teachers. To make that effort successful, the district used federal Elementary and Secondary School Relief (ESSER) funds to pay teachers for the additional teaching time and to purchase supportive instructional materials to build personalized, targeted instruction for each student during the 30-minute block.

Keys to Success: Intentional planning, continual assessment

Longley and his team spent a significant amount of time planning for the added intervention block.

“It was a highly personalized, very specific dosage of instruction we were providing,” Longley said. “Specific goals, content, and conferencing with students were all p

art of our process.”

art of our process.” Longley and his team made sure continual assessment of student progress toward academic recovery was a central component of their plan. Longley also spent a portion of the pandemic emergency relief funds hiring staff to work one-on-one with students identified for intensive support.

At first, individual student progress varied, Longley said.

“Some students…all they needed was those first 9 weeks,” he said. “And then they took off. Some kids took longer than that.”

The added time to focus on student learning gaps provided much-needed validation for teachers, whose jobs the pandemic made significantly more challenging.

“The teachers celebrated the fact that we were saying [that] we understand that there are gaps, and we want to give [them] the time to address them,” Longley added.

The result: “A high-level educational experience that we had not had the opportunity to offer prior,” Longley said.

The intentional, personalized approach rooted in continual assessment has paid off: Since 2022, both student attendance and math proficiency on the Georgia Milestones state assessment have doubled. For a school whose students were scoring near the bottom among all Atlanta Public Schools before the pandemic, those are significant achievements.

“We may not be in the front yet,” Longley said, “but we’re gaining speed and narrowing that gap.

District dials back after ESSER funds dry up

But the federal pandemic emergency school funding that made it possible to pay teachers for the additional teaching, planning, and one-on-one student conference time and to pay for additional staff and instructional materials is gone.

Consequently, the school system had to revert to its regular 6.5-hour school day for the 2024-25 school year.

Some schools still implement the 30-minute intervention block, but it’s no longer mandatory.

“We had to make some tough decisions: How do we make this sustainable when the money isn’t here?” Longley said.

The loss of the 30-minute intervention block and the sunsetting of ESSER funds are formidable challenges for Longley and his staff.

Still, they haven’t stopped striving for their students. They continue to center instruction on the materials purchased for the intervention block. They’re also leveraging the know-how they gained while implementing the 30-minute block by creating new intervention spaces within regular classes during their now 6.5-hour school day.

“The knowledge is still there, and the devices, the computers, the iPads, the instructional materials,” Longley said.

But Longley and his team are still squeezed for time. That means the pace of student learning growth has slowed, and staff morale has suffered.

“Getting that extra time for students…teachers felt heard. But now we’re back to trying to figure out how we can get all of this in,” Longley said.

The principal is also worried that possible efforts by the Department of Education to decrease federal funding for K-12 education might mean even fewer resources to help students—regardless of their previous achievement levels, socioeconomic status, or race—make academic progress.

“Previous achievement levels, the neighborhood community economics, those did not impact the effectiveness of these initiatives,” Longley emphasized. “These initiatives were effective across the board…for students of all races, for parents, for teachers, and for the community.”

Media Contact:

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Media Contact:

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000

Contact Name

Contact@email.com

(000) 000-0000